The essay Meléta: Epicurus’ Instructions for Students inspired a second part, and I continued to refer to it over the years. Here, I’d like to revisit it and focus on the words upar and onar (while awake and while sleeping), and how they relate to the rest of the Meleta portion of LM, and to VS 11, in order to help sincere students and practitioners of Epicurean philosophy to organize themselves around their practice.

Notice that the recommended ways of practicing here are tied to the rhythms of nature. Just as there is a lunar cycle tied to the communal feast of Eikas (which was, in the original lunar calendar, a waning moon feast), similarly there is a solar cycle, a circadian rhythm involved in the praxis recommended in the meleta portion of the Epistle to Menoeceus. Let us look at the relevant passage:

So practice these and similar things day and night, by yourself and with a like-minded friend, and you will never be disturbed whether waking or sleeping, and you will live as a god among men: for a man who lives in the midst of immortal goods is unlike a merely mortal being. – Epicurus’ Epistle to Menoeceus

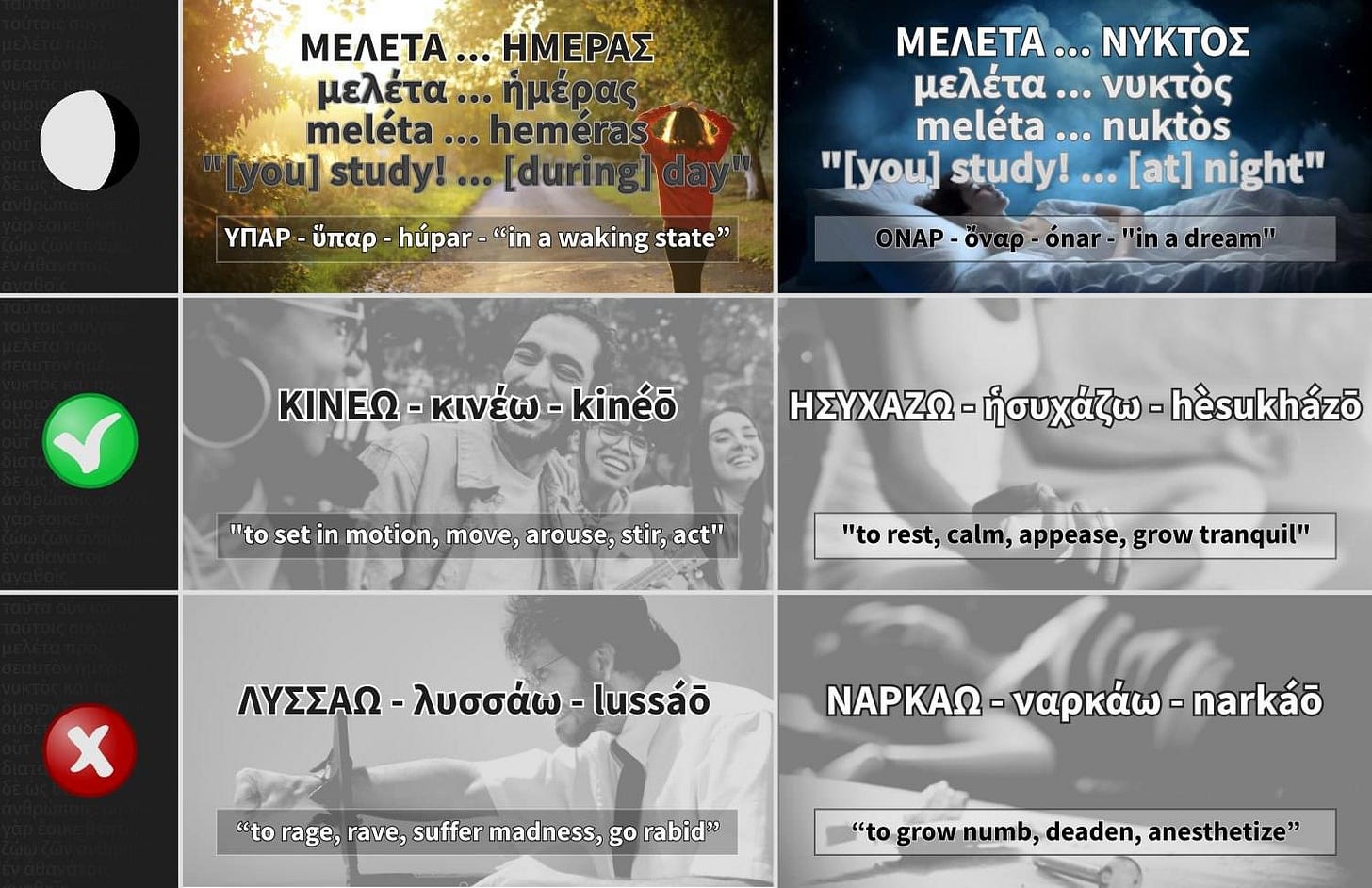

The context of the passage is that there is a big IF tied to Epicurus’ promise that we will live like gods among mortals: this transcendental quality of life can be attained if, and only if, we practice according to the instructions given. One condition is that we must be surrounded by immortal goods (which includes friendships, and other blessings). The other condition is what ties praxis to the circadian rhythms. The words used for day and night are imeras and nuktos.

Here, Epicurus is recommending two distinct practices: imeras meleta (day-time philosophical practice or deliberation) and nuktos meleta (night-time philosophical practice or deliberation). Based on the reference to never being perturbed, the goal of these practices is to arm ourselves against the different types of perturbations that might visit us during waking hours, and those that might visit us during sleep or time of rest. It’s up to each individual to consider what this means for them. Many or perhaps most of us already have some ritual or mental and bodily preparation that we use at the beginning of the day (coffee in the morning), and before bed (de-stressing from work, night-time tea, etc.), and Epicurus is inviting us to incorporate philosophy into these circadian rituals.

Activity and Rest

For most people, to be quiet is to be numb and to be active is to be frenzied.

τῶν πλείστων ἀνθρώπων τὸ μὲν ἡσυχάζον ναρκᾷ, τὸ δὲ κινούμενον λυττᾷ.

The epicurus.net translation says “Most men are insensible when they rest, and mad when they act”.

In VS 11, the Kathegemones teach that there is a correct and incorrect way of engaging in activity, as well as a correct and incorrect way of engaging in rest.

In this saying, we see a juxtaposition of ἡσυχάζον (hesuchazon, rest, quietude, leisure) with ναρκᾷ (narka, numbness, senselessness), and κινούμενον (kinoumenon, activity) with λυττᾷ (lytta, agitation, madness) where we are told that one is not the same as the other. The saying implies that the first one (hesuchia, kinoumenon) is a practice of living correctly and pleasantly and the second one is not.

Therefore, if we find the opposite or negation of narka and lytta, we will likely begin to come up with ideas that tie to correct, Epicurean hesuchia and kinoumenon. For instance, the narcotized state of numbness would be countered by a present, clear-minded sobriety which would therefore characterize true hesuchia. The restless, mindless, and perhaps aimless agitation of lytta would be countered with mindful, focused, intentional, calm action, which would therefore characterize correct activity or true kinoumenon.

I link both narka (insensible, narcotic idleness) and lytta (agitation, anxiety in action) to mindlessness. The medicine for both diseases of the soul (and the practice of this saying), therefore, is the mindful practice of regulatory methods or techniques to cultivate a correct disposition in both action and leisure.

A Deliberation on KD 14 and LM

The use of the term ἡσυχάζον (hesuchazon) ties this saying to Principal Doctrine 14, which uses the term ἡσυχίας (hesuchias) to refer to aloneness, solitude, the practice of quietude.

Since we know that the Vatican Sayings were compiled after Epicurus died (they mention him in the third person after he has died, as if his life had already become a legend), we can surmise that VS 11 is meleta or commentary by the Kathegemones that seeks to clarify the previous teaching concerning hesuchia, after careful deliberation among friends.

This saying ties to “sober reasoning” in the Letter to Menoeceus, and is part of (among other things) an Epicurean praxis of sober pleasures.

A Wisdom of Leisure

The word ναρκᾷ (insensible) translates as “without one’s mental faculties, typically as a result of violence or intoxication; unconscious”. It also translates as “unaware of, indifferent to”.

This points to an Epicurean wisdom of rest, leisure or quietude which must differentiate the philosopher from the numb and insensible. If we accept the argument that pleasure always has content, context and causes, then we may add a book, or a practice of abiding in the breath, or a song, or some other technique, as a way to practice VS 11. This is not to say that Epicureans are merely “hermits” or “ascetics” necessarily, although Epicurus did practice intermittent fasting, and KD 14 seems to indicate that some measure of “laughing-hermit” practice is healthy for the soul.

A Wisdom of Activity

VS 11 also says that most men are mad (λυττᾷ; lytta) when they act. It’s up to us to figure out the signs by which we may diagnose this problem of agitation, anxiety, or an unsettled disposition.

In the realm of activity, Vatican Saying 41 supplements this saying by placing before our eyes ways to practice managing our disposition, mentality, or attitude (with the help of a laughter practice) while remaining pragmatically engaged in action and speech. The following visual is courtesy of our friend Nathan.

Conclusion

In Vatican Saying 11, we read a general concern for the quality of our sentience, both in leisure and in activity, which I believe serves to clarify and elaborate on Epicurus’ mention of upar and onar—and his recommended daily and nightly practice—in the Epistle to Menoeceus. While the saying does mention at least two bad habits or diseases of the soul, it remains up to us to figure out the signs by which we diagnose them and the medicines or disciplines of the self by which we treat them, and by which we maintain correct practices of leisure and activity.

Very good. Thanks, Hiram.